Obesity, dieting and weight loss – what do we know?

In Part 1 of this series, we looked at the effectiveness of weight loss programs and diets by people who feel fat and want to lose weight. We concluded that losing weight is not the solution. Even after losing weight, guilt, deprivation and “feeling fat” can persist. The solution is to acquire the skills to control when you start eating and when you stop eating.

In Part II of this series, we looked at what it is that starts and stops us from eating – the determinants of eating behaviour – and why it is that we have to eat in the first place. We will discover that “the real problem” has nothing to do with willpower.

In Part III of this series, we will look at the extremely complex internal mechanism that regulates our eating behaviour.

PART III: The Internal Automatic Regulatory Mechanism (ARM)

We now recognize that the balance needed for the existence of life is extremely ‘delicate’ and that the control of this balance is simply too important to be left to conscious control. To think that humans regulate their weight and their food intake by consciously thinking about it and making calculated decisions, is simply absurd. It is important to keep these things in perspective.

Obviously, there must exist some type of mechanism – a regulator – which controls the balance of energy. The analogy which is often made is to a thermostat in your house. The thermostat in your house controls the temperature of your house or the quantity of heat in your house. It does this by measuring the temperature – a measure of heat energy. Something in the thermostat – a type of metal or mercury or some other substance – changes with temperature (it expands or contracts) and this can turn on a switch which turns on the furnace which generates more heat. When heat is generated and the temperature rises, it changes the thermostat which in turn shuts off the switch.

This is known as a “negative feedback system”. That is, the more the furnace works, the more it shuts itself off.

A similar system must be operating in your body. When you need energy, something measures the need and turns on ‘hunger’- the drive to eat. This is also a negative feedback loop in that the more food you consume, the less eating you should want to do – eating should shut itself off. When there is enough energy, eating is shut off – i.e. ‘satiety’

But how does this system work? Let us look at this in more detail.

What Is Being Controlled

In your house we know that what is being controlled (the controlled quantity is heat as measured by the temperature of your house). But what is it that is being controlled in your body? Think about it. What is it in your body that is being measured and controlled? Is it your body weight? Is there something inside which can measure your body weight and when you begin to lose weight you start to eat and as you gain weight you are compelled to stop eating? Or is it your body temperature? Or is it energy in general, as measured by calories? What is it?

Before we begin to try to answer this question, let us look at some of the research studies that have been done so that we can get a better idea of just how well the system works and what affects it. The studies that will be discussed here are just a very brief summary of the many studies that have been done with a variety of different types of animals as well as with humans.

The first step is just to gather more information so that we can get a better idea about what is going on.

- Random Diet

What do you think would happen if you take animals (e.g. laboratory rats) and give them a ‘cafeteria’ diet? That is, if you give them many different types of foods that they can partake of freely in a fairly comfortable and relaxed environment. You could give them chocolate chip cookies, bananas, specially prepared well-balanced laboratory diets, and all sorts of other foods that humans eat.

What do you think happens when animals are put into such environments and allowed to eat as much as they wish at any time? Do you think that they gain weight? Lose weight? Binge on only specific types of foods? Maintain a well-balanced diet? Maintain their weight? What do you think?

Well, unless the circumstances are very abnormal or extraordinary, you would find that the animals tend to eat a well-balanced diet, maintain their caloric intake and maintain their weight. The regulator works very accurately under these circumstances.

- Artificial Weight Gain

Animals can be made to gain weight artificially through a number of means including such things as force feeding (as is done with geese and other animals which are bred to produce certain types of foods) or through injecting insulin which increases the uptake if sugar and causes animals to eat more and gain more weight. What do you think happens when animals who have had their weight artificially raised are allowed to eat food freely without continued insulin injections or force feeding? Do you think that they continue to gain more weight? Maintain their elevated weight? Lose weight?

Animals in this situation will decrease their food intake below what they normally eat until their weight decreases and levels off back within a normal range. They will then maintain their food intake and caloric intake at an appropriate level to maintain their weight.

The regulator continues to work! Even when animals are made artificially fat, their weight returns to normal and their eating is maintained at an appropriate level.

- Artificial Weight Loss

Animals can be made to lose weight by decreasing the amount of food they are given – i.e. depriving them. What do you think happens when rats are artificially made to lose weight by being deprived of food and then given their food back freely? Do you think they continue to maintain a lower weight? Do you think they gain weight?

When allowed to eat freely again, the animals actually increase their food intake beyond their regular levels until their weight comes back into the normal range. They then level off their caloric intake to maintain their weight within the normal range.

Again, the regulator works very accurately even if you try to trick the system by artificially decreasing body weight.

- Caloric Dilution

It is possible to dilute the number of calories in an animal’s food by adding non-nutritive bulk such as cellulose to dry food or water to a liquid food like Metrecal. What do you think happens to the rats if you dilute their food in half by adding non-nutritive bulk? Obviously, in order to eat the same number of calories they would have to eat twice the quantity of food. Do you think the animals eat more? Eat less? Eat the same? Do you think they gain weight? Lose weight? Stay the same?

Studies clearly demonstrate that animals increase the amount that they eat in relation to how much you dilute to food. If you dilute the food in half, they eat twice as much. They maintain their caloric intake at a constant level; they maintain their weight; and the regulator continues to work even though they have to eat twice as much.

- Concentrate Calorie

It is possible to increase the number of calories in an animal’s food (the calorie density) by mixing very high caloric substances in with the regular food. For example, one can include glucose in with the regular food. In fact, animals prefer this mixture if given a choice between their regular food and food mixed with the sugar solution. But now, the same quantity of food has significantly more calories. What do you think animals do in this situation? Do you think that they eat more food and gain weight, or do you think they eat less food and maintain their weight?

Again, the regulator works! Animals in this situation, even when presented with food that they find appealing and prefer, will actually decrease the total amount that they eat in order to maintain a constant caloric intake and maintain their weight.

- Aversive Flavour

Obviously, one factor which affects eating is the taste of the food. Just as sugar makes the food more appealing or preferred, the same food can be made less appealing and even aversive by adding some substances. Quinine, for example, is an extremely bitter substance which animals and humans find very distasteful if added even in small amounts. If you add a very small amount to the regular food of a rat and give the rat a choice between a quinine adulterated food and another food, the rat will never eat the quinine flavoured food. However, what do you think the animal does if you don’t give it a choice and it only has the quinine flavoured food to eat? Do you think it eats less? Do you think it eats the same? Do you think it loses weight?

Well, as you may have guessed, the animals will continue to eat the same caloric quantity even though they appear to hate the food – to the point where the food literally becomes poisonous and makes them ill. The regulator works again! Animals will continue to eat the number of calories required to maintain their weight even when the food is very aversive and bad tasting.

In summary, therefore, we can see that the regulator works very well indeed. Even when extraordinary attempts are made to ‘trick’ the system, the system still works very accurately. While there are always exceptions, this is generally the rule for all animals under normal situations and, if you think about it, it is true for most people as well.

How does it work?

It is quite clear that caloric intake is being regulated very carefully. So is weight. The question is now, how does it work? If you were going to build a system inside the body to monitor and regulate the caloric intake, how would you do it?

Going back to our example of a thermostat in the house, we know that mercury expands with increased quantity of heat (temperature). The mercury will vary exactly with the amount of heat – the quantity we wish to control – and we can connect a switch to the mercury level and consequently it is easy to measure and control the amount of heat in our house.

But how would we measure the amount of energy being taken in or used up by our body? What would be equivalent to that column of mercury in our body? What system or systems in our body do you think could be used to tell us when we need or do not need energy?

This very question has been the centre of much interest for more than 100 years of scientific investigation. There are volumes written about this. Let’s just look at some of these briefly.

- Gastric Motility – Stomach

The stomach and its activities is an obvious possibility. Stomach ‘growling’ and sensations are frequently associated with ‘hunger pangs’. Not surprisingly, this was one of the earliest areas of research. Many years ago some researchers felt that hunger was in fact simply the sensations of stomach contractions.

While there is absolutely no doubt that the stomach plays a very important role in controlling and monitoring our eating, there is already some evidence that indicates that the stomach, by itself, cannot be the controlling factor.

Remember what we observed with our rat? When food is diluted of calories, the animals eat much more. Stomach distention by itself, therefore, cannot be the ruling factor. In addition, there is clear evidence that humans with partial removals of their stomachs as well as those with denervation of their stomachs regulate their weight very well, although meal patterns change somewhat.

Therefore, the stomach, although it may be important, is by itself not even necessary for accurate regulation.

- Oral pharyngeal Factors

The mouth and throat, chewing and swallowing, taste and smell, all play significant roles in affecting our eating. There have been numerous studies which indicate a significant involvement of all of these factors.

For example, the simple acts of eating and swallowing alone, even without the food entering the stomach, will have the effect of stopping the eating of an animal (for a short term). Similarly, our taste buds are affected by many aspects of the physiological condition of our body, including our specific needs for various nutrients or what we have just eaten. This in turn influences how different things taste to us – sweet, salty, good or bad – and consequently affects our ‘appetite’ for different types of food. It has also been demonstrated, for example, that when certain substances such as sugar are taken into the mouth, these substances may permeate the lining of the mouth and actually enter into the blood and brain well before the food becomes digested in our stomachs. This allows our brain to monitor what we are eating very rapidly.

However, other studies indicate that actually eating the food is not even necessary for maintaining caloric regulation and weight. Studies on animals with tubes inserted directly into their stomachs indicate that animals will learn to press levers to have food injected directly into their stomach without even tasting or swallowing the food. These animals will maintain appropriate caloric intake and maintain their weight. Even if you dilute their food, they will increase their intake appropriately.

Therefore, although oral pharyngeal factors are clearly important and significant, they also cannot fully explain how the system maintains caloric intake and weight regulation.

- Body Temperature

The various temperatures of different parts of our bodies have a major effect on our eating behaviour. When our ‘core’ (deep internal body) temperature rises, eating behaviour becomes inhibited. For example, when people have fevers, there is a definite suppression of appetite. The relationship between core temperature, brain temperature, and body surface temperature is quite complex and its effect on eating is also very complex and unclear.

However, there is also evidence which indicates that temperature and eating can be separated. For example, many drugs which are used to supress appetite actually decrease temperature. So it can be seen that body temperature and eating behaviour can be separated and temperature by itself cannot be the controlling factor.

- Lipostatic – Fat Metabolism Rates

There have been suggestions that the metabolism of fat in our body is a critical factor in affecting our eating behaviour and the regulation of calories. We already know that when we have excessive calories, physiological changes can take place to convert excess sugar into fat. When we require energy and have a deficit of readily available calories, our physiology shifts in the other direction to convert fat to sugar. There have been some suggestions that this mechanism itself is the critical factor indicating hunger (fat to sugar) and satiety (sugar to fat). The most obvious limitation with this particular theory is that the process is so slow it would not begin to stop eating during a meal until far too many calories had been consumed. Therefore, while this metabolic cycle may in fact be important, it by itself cannot account for the precise and delicate control of eating behaviour and caloric regulation.

- Blood Borne Factor

It has been well known for many years that factors in the blood affect eating behaviour. There have been numerous studies which have shown that such things as infusing the blood of a hungry animal into the body of a satiated animal will cause that animal to begin eating.

While there are numerous possibilities as to what these various blood-borne factors might be, one obvious factor is the blood glucose (sugar) level. The ‘glucostatic’ theory suggests that the amount of sugar in the blood controls whether a person is hungry or satiated. Increasing the amount of sugar in the blood of an animal which is eating will cause eating to stop. However, there is no relationship between the amount of sugar in the blood and the beginning and cessation of eating.

The glucose utilization (A/V ratio) suggests that the critical factor is not the absolute concentration or amount of sugar in the blood, but rather the amount of sugar in the arteries (the blood vessels that take the blood to the cells of the body to nourish them) and the amount in the veins (the blood vessels which take the used blood away from the cells). Obviously, if your body does not need energy and is not using sugar, the amount of sugar in the arteries will be the same as the amount of sugar in the veins. However, if your body does need energy and is using sugar to provide that energy, then the amount of sugar in the arteries will be greater than the amount of sugar in the veins. There is a good relationship between this ratio and onset and cessation of eating behaviour.

However, there are problems with these theories as well. Diabetics who have notoriously high blood sugar levels are also well known for having voracious appetites. The fact is, that eating behaviour and blood sugar levels can be separated and although this is clearly an important factor, it too by itself cannot be the only factor which controls and regulates our caloric intake, our eating behaviour and consequently, our weight.

- Brain – Hypothalamus

It is obvious that our brain is intimately involved in the control of eating behaviour. In particular, a small area of the brain known as the hypothalamus is critical in controlling and integrating not only our eating behaviour, but other behaviours such as drinking, temperature regulation, and other behaviours critical for survival.

So what is the conclusion? It is obvious that the regulator – the internal automatic regulatory mechanism (ARM) – is expectedly complex. Although a great deal is known about this, it is still poorly understood.

The regulation of eating behaviour is even more complicated than simply regulating calories. For example, the body must also carefully control the balance of salts and water, and what we eat affects this. If, for example, the concentration of salts in our bodies is too high, and we do not have enough water, we become thirsty. However, if there is no water available for us to drink, it would be detrimental for us to eat foods. That would increase the salt concentrations in our body. Consequently, when we are in need of water, there is an active suppression of appetite. There is decreased eating. Similarly, temperature regulation also plays an important role. Since it is critical that our temperature levels are carefully guarded and that our concentrations are maintained in addition to our energy balance, all of these factors interact in an extremely complex way.

The fact is that the system is simply too complicated to be left to our willpower or conscious control. To think that humans regulate their weight and their food intake by consciously thinking about it and making calculated decisions, is simply absurd. The internal automatic regulatory mechanism cannot be corrected and there is no magic solution.

In Part IV of this series, we will discover the solution to the problem. At the present time, the solution may not appear to be obvious to you and you may not have the skills. But, be patient, the solution will become obvious and the skills are easily acquired.

SOURCES

Chaput JP, Tremblay A. (2008, November 11). The glucostatic theory of appetite control and the risk of obesity and diabetes. International Journal of Obesity. Doi:10.1038/ijo.2008.221

Garcia, J., Hankins, W., Rusiniak, K. (1974, September 6). Behavioral regulation of the milieu interne in man and rat. Science. Vol. 185, Issue 4154, pp. 824-831. DOI: 10.1126/science.185.4154.824

Jordan, H. A. (1969). Voluntary intragastric feeding: Oral and gastric contributions to food intake and hunger in man. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 68(4), 498-506. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0027664

Stunkard, A., Fox, Sonja. (1971, March). The relationship of gastric motility and hunger: A summary of the evidence. Psychosomatic Medicine

White, C, Purpera, M, Ballard, K, Morrison, C. (2010, June 6). Decreased food intake following overfeeding involves leptin-dependent and leptin-independent mechanisms. Physiology and Behavior, Volume 100, Issue 4, Pages 408-416

Recently, I decided to investigate the current scientific literature regarding behavioural approaches to eating control and weight regulation. I discovered the work of Dr. Brian Wansink, (Ph.D. Stanford 1990) who is the John Dyson Endowed Chair in the Applied Economics and Management Department at Cornell University, where he directs the Cornell Food and Brand Lab. He is the lead author of over 100 academic articles and books on eating behaviour. Kelly D. Brownell, Yale University, has hailed Dr. Wansink as “the Sherlock Holmes of food”.

Recently, I decided to investigate the current scientific literature regarding behavioural approaches to eating control and weight regulation. I discovered the work of Dr. Brian Wansink, (Ph.D. Stanford 1990) who is the John Dyson Endowed Chair in the Applied Economics and Management Department at Cornell University, where he directs the Cornell Food and Brand Lab. He is the lead author of over 100 academic articles and books on eating behaviour. Kelly D. Brownell, Yale University, has hailed Dr. Wansink as “the Sherlock Holmes of food”.

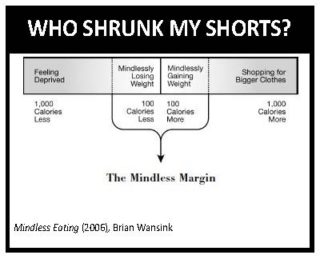

It has been a LONG winter and now the sun is shining and you want to enjoy the outdoors. You pull out your favourite pair of shorts and pull them on. What the heck!!!!!! WHO SHRUNK MY SHORTS? Don’t worry, you are not alone! You may ask yourself whether your partner washed them in hot water or you may wonder if these shorts belong to your skinny sister. But deep down inside, you know that it is not the shorts that shrunk, but you who has grown bigger.

It has been a LONG winter and now the sun is shining and you want to enjoy the outdoors. You pull out your favourite pair of shorts and pull them on. What the heck!!!!!! WHO SHRUNK MY SHORTS? Don’t worry, you are not alone! You may ask yourself whether your partner washed them in hot water or you may wonder if these shorts belong to your skinny sister. But deep down inside, you know that it is not the shorts that shrunk, but you who has grown bigger.