Have you ever thought about what the world would be like without rules, contingencies, stipulations, regulations, or facts? In my opinion, although it may be fun at times, it would be chaotic, potentially dangerous, full of ambiguity, and disorganized. In a world of about 7 billion human beings, all with very different values, goals, ideas, and personalities, we need structure and boundaries – we need RULES. Rules serve many purposes, but ultimately, they promote safety, protection, peace, fairness, and an overall well-being for all abiders.

Quite understandably our minds, being such a powerful and intelligent organ, instinctively opts for this same safety, organization, and protection. It protects us from danger by reminding us not to run on a broken leg or step in front of an approaching train; it helps us stay organized by telling us that although we may like to go out for lunch, we have a meeting at work starting in five minutes; and it helps us maintain peace or well-being by kick-starting our inhibitions and reminding us of the consequences of our actions, like what may happen if we use physical violence during a disagreement. Unfortunately, however, the mind’s rule-setting, boundary-creating, and protection-ensuring mechanism is not always ‘positive’. It can cause us to unnecessarily restrict our lives and limit ourselves as well.

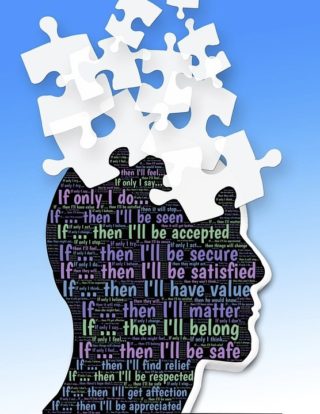

Our mind can be quite selfish, although its intentions may be good. When it perceives a threat, it goes into protection mode, as described in the examples above, and it does not often think beyond that. Although this helps us immensely in many of our interactions with the external world, it is when it tries to protect us from experiencing our uncontrollable internal content that it can make us feel, or act, defeated. Our internal content consists of our thoughts, feelings, and emotions. For example, if we struggle with social anxiety, our mind may instinctively try to protect us by encouraging us to avoid feeling this anxiety, which may only be achieved by avoiding any social interactions altogether. If we struggle with chronic pain, our mind may try to help us limit this pain (since it has learned to perceive pain as a threat) by encouraging us to avoid any type of physical activity or movement that may (but more likely will not) cause harm or damage. When faced with difficult internal content, our mind starts to create rules, stipulations, and limitations, which are often statements with BUT’S and IF and THEN’s that we are all very familiar with.

Our mind can be quite selfish, although its intentions may be good. When it perceives a threat, it goes into protection mode, as described in the examples above, and it does not often think beyond that. Although this helps us immensely in many of our interactions with the external world, it is when it tries to protect us from experiencing our uncontrollable internal content that it can make us feel, or act, defeated. Our internal content consists of our thoughts, feelings, and emotions. For example, if we struggle with social anxiety, our mind may instinctively try to protect us by encouraging us to avoid feeling this anxiety, which may only be achieved by avoiding any social interactions altogether. If we struggle with chronic pain, our mind may try to help us limit this pain (since it has learned to perceive pain as a threat) by encouraging us to avoid any type of physical activity or movement that may (but more likely will not) cause harm or damage. When faced with difficult internal content, our mind starts to create rules, stipulations, and limitations, which are often statements with BUT’S and IF and THEN’s that we are all very familiar with.

“I want to attend my best friend’s wedding, but I am too anxious” or, “If my anxiety goes away, then I can go to my best friend’s wedding”.

We tend to place a great deal of trust in our mind and we absorb these rules as facts and follow them to the letter, causing us to lose sight of our values and stop acting in accordance with such values. Our mind can convince us that it is more important to protect ourselves from feeling anxiety than to attend our best friend’s wedding, even if the latter is very important to us.

Learning to be able to hear what the mind has to say, but not always listen to its rules is neither easy nor quick. It takes time to be able to decipher between actual threats and perceived threats. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) offers a few exercises to help with this. One simple, yet powerful ACT exercise is to replace all self-referential ‘but’s’ with ‘and’s’. So from our example above, we may instead say to ourselves,

“I want to attend my best friend’s wedding, and I feel anxious about it.”

Now the statement is not limiting and is rather a statement composed of two independent facts, the first no longer being contingent on the second.

Try it yourself. Keep record of any ‘but’ thoughts your mind produces, and replace the ‘but’s’ with ‘and’s’. Take the exercise one step further by taking an action that the ‘but’ may have stopped you from taking. For example, in the case of our best friend’s wedding example – attending the wedding despite the anxiety would be the next step.

![]()

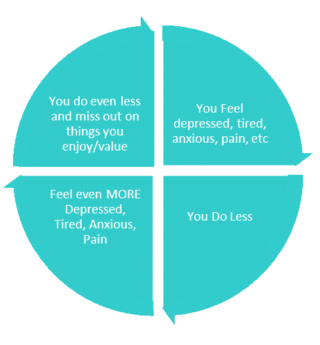

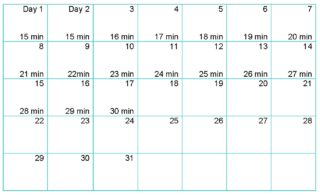

The trouble is that when we are facing depressive or anxious thoughts, going for a walk is not the first thing that comes to mind. For most people who suffer with mental health, it is quite the opposite: you may feel like doing less and avoid doing the things that are of value to you. The problem is, when you do less, you feel the impact of the symptoms even more and continue to miss out on living a meaningful life. This is a common cycle for most people, but it can be broken. Behaviour Activation (BA) can help disrupt the above stuck loops by introducing positive behaviours. Walking is an ideal behaviour to introduce as it has so many benefits for mental well-being. Improvements in mood and energy can be noticed almost immediately. Over time, many other benefits can be noticed, including:

The trouble is that when we are facing depressive or anxious thoughts, going for a walk is not the first thing that comes to mind. For most people who suffer with mental health, it is quite the opposite: you may feel like doing less and avoid doing the things that are of value to you. The problem is, when you do less, you feel the impact of the symptoms even more and continue to miss out on living a meaningful life. This is a common cycle for most people, but it can be broken. Behaviour Activation (BA) can help disrupt the above stuck loops by introducing positive behaviours. Walking is an ideal behaviour to introduce as it has so many benefits for mental well-being. Improvements in mood and energy can be noticed almost immediately. Over time, many other benefits can be noticed, including:

Steven Hayes is widely considered to be one of the founding fathers of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and has authored over 400 academic publications! Get Out of Your Mind & Into Your Life applies concepts of ACT to help readers move from feeling stuck in a struggle against their own minds to assess what is truly meaningful to them and then pursue a life guided by those values.

Steven Hayes is widely considered to be one of the founding fathers of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and has authored over 400 academic publications! Get Out of Your Mind & Into Your Life applies concepts of ACT to help readers move from feeling stuck in a struggle against their own minds to assess what is truly meaningful to them and then pursue a life guided by those values.