Statistics Canada says close to a third of Canadian kids under 17 are overweight or obese. The rising prevalence of overweight and obesity in several countries has been described as a global pandemic. In 2010, overweight and obesity were estimated to cause 3.4 million deaths, 4% of years of life lost, and 4% of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) worldwide. Data from studies in the USA have suggested that, unabated, the rise in obesity could lead to future falls in life expectancy. Concern about the health risks associated with rising obesity has become nearly universal; member states of WHO introduced a voluntary target to stop the rise in obesity by 2025, and widespread calls have been made for regular monitoring of changes in the prevalence of overweight and obesity in all populations[1].

It is more apparent than ever that losing weight is not an achievable goal for the majority of people. As incredible as it sounds, that’s what the evidence is showing. For psychologist Traci Mann, who has spent 20 years running an eating lab at the University of Minnesota, the evidence is clear. “It couldn’t be easier to see”, she says; “long-term weight loss happens to only the smallest minority of people”. Traci Mann’s research on long term weight loss shows that on average, dieters only maintain a 1 kilogram weight loss over two years.

One solution would be to prevent weight gain in the first place. “An appropriate rebalancing of the primal needs of humans with food availability is essential”, University of Oxford epidemiologist Klim McPherson wrote in The Lancet[2]. But to do that, he suggested, “would entail curtailing many aspects of production and marketing for food industries”. As necessary as this may be, it is certainly not a “quick fix” solution.

Have you ever dieted? Did you lose weight? Did you gain it back? Why are we obsessed about doing something that has been proven over and over again to not work? There is an alternate approach, and believe it or not, it has been around for at least 35 years.

The SHAPE (Strategies for Healthful and Pleasurable Eating) Eating Control Program was developed by Dr. Arthur Cott and his colleagues at the Behavioural Medicine Unit (BMU), St. Joseph’s Hospital, Hamilton, Ontario, in the early 1980’s. Dr. Cott’s approach utilized the scientific evidence in the learning theory literature to design a comprehensive educational program for individuals who felt fat, wanted to lose weight and were fed up with the numerous diets, both mainstream and fad, that they had unsuccessfully endured. I was privileged to be one of those who worked with Dr. Cott and would like to share his wisdom with you.

The SHAPE Program was a 24 week course that combined both lectures and small group tutorials. The students in the course ranged in age from 16 years to 70 years. Both males and females paid a hefty registration fee to attend this course which was taught at locations in Hamilton, Toronto, Kitchener and St. Catharines over a 10 year period. The lectures were delivered by Psychologists from the BMU, including Dr. Arthur Cott, Dr. Harvey Anchel and Dr. Richard Marlin. The tutorials were led by Behavioural Therapists who had been trained and

specialized in the application of cognitive behavioural therapy for chronic somatic and mental health conditions as well as behavioural issues, such as eating control. Again, I was fortunate to have been a tutorial leader and eventually, the Manager of the SHAPE Program.

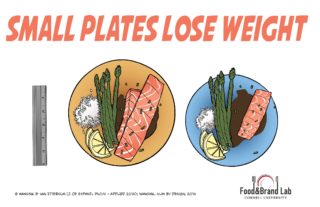

Recently, I decided to investigate the current scientific literature regarding behavioural approaches to eating control and weight regulation. I discovered the work of Dr. Brian Wansink, (Ph.D. Stanford 1990) who is the John Dyson Endowed Chair in the Applied Economics and Management Department at Cornell University, where he directs the Cornell Food and Brand Lab. He is the lead author of over 100 academic articles and books on eating behaviour. Kelly D. Brownell, Yale University, has hailed Dr. Wansink as “the Sherlock Holmes of food”.

Recently, I decided to investigate the current scientific literature regarding behavioural approaches to eating control and weight regulation. I discovered the work of Dr. Brian Wansink, (Ph.D. Stanford 1990) who is the John Dyson Endowed Chair in the Applied Economics and Management Department at Cornell University, where he directs the Cornell Food and Brand Lab. He is the lead author of over 100 academic articles and books on eating behaviour. Kelly D. Brownell, Yale University, has hailed Dr. Wansink as “the Sherlock Holmes of food”.

Clearly, Dr. Brownell had never met Dr. Cott. I very quickly discovered that Dr. Cott’s approach from 35 years ago is just as relevant today as it was back then. I had always believed that this approach was remarkable in its interpretation and implementation of science. Now I know that it has survived the test of time. Dr. Cott’s approach was truly ahead of its time.

At one point, the SHAPE program was featured in one of our Canadian magazines which resulted in an overwhelming response from readers across Canada who wanted to participate in the program. To meet this need, those of us at the BMU at the time, made a decision to develop a “correspondence course” version of the program. Being the pack rat that I am, I am extremely fortunate to have a copy of the course content developed by the BMU and I would like to start sharing it with you now. This is the first of a 4 part series (check out our blog each week to find the rest!).

PART I: WHAT IS THE REAL PROBLEM?

Believe it or not, even though many people think they have a weight problem, weight is not really the problem. Look at the following examples. All of these people thought they had a weight problem. Does any of this sound familiar to you?

Maryanne is a 41-year old, full-time health care professional, married with 2 school-age children. She’s been fat and she’s been skinny. She has waged a constant battle over the last 10 years in her attempts to control her body weight. She has tried low-fat diets, low-carb diets and counting calories. Maryanne has struggled with frustration from Scarsdale to Pritikin to Beverly Hills Diets. Some of them worked… for a while. “I lost 44 lbs in 6 weeks and I’ve put it all back on” comments Maryanne.

Bill is 48 years old, married with 3 grown children, all of whom are living away from home. The nature of his occupation, a senior manager in the steel industry, requires him to make several business trips a year and to attend numerous business functions, usually all associated with eating. The impetus for Bill to do something about his weight had come from his family physician who had been treating him for the past year for elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Bill had been monitored for 12 months as he attempted to stay on a prescribed diet, which included very few of his favourite foods. Bill was discouraged and fed up with the ‘diet’, but still concerned about potentially serious health problems.

Elizabeth had dieted for at least 25 of her 30 years, attending every kind of group dedicated to losing weight. She knows she’s fat while others claim she’s skinny. She claims to have lost “at least 1000 lbs” and spent hundreds of dollars on diets. For the past 2 years she has successfully maintained her weight at 120 lbs. At 5’3” tall, Elizabeth appears to be a ‘normal weight’ person. Elizabeth describes herself as ‘fat’. She believes that her primary goal is to lose weight and listed her ideal weight as 110 lbs.

Each of these three people has one or more of the following problems:

- “I feel fat!”

- “I just look at banana splits and donuts and gain weight”

- “I am always hungry”

- “eating desserts makes me feel guilty, but when I don’t, I feel deprived”

- “nothing seems to fit”

- “I must be addicted to food. Once I start eating peanuts, I can’t stop”

- “I’m always on a diet”

- “whenever I’m on a diet, my family loses weight”

- “going to the beach means wearing sweat pants and t-shirts, never a bathing suit or shorts”

The question is, what do any of these problems have to do with weight? The answer is NOTHING! Weight is not the problem. Weight is simply the result or outcome of the problem. The problem is lack of control of eating. Your eating is controlling you – you are not in control of your eating.

Many of us complain of feeling guilty after eating certain kinds of foods. Questions such as “should you be eating that?” or “is that in your diet?” are frequently heard as family members comment on what we are about to eat. Some individuals report that the guilty feelings are so strong that they avoid eating in public as much as possible. Instead, they consume large quantities of their favourite foods when they can be certain of no interruptions.

A second characteristic frequently demonstrated by people with eating problems, especially the constant dieter, is that of deprivation. While everyone else is enjoying steak with béarnaise sauce, baked potato with sour cream and apple pie a la mode, the dieter is suffering with a tossed salad and no dressing, broiled fish and water. Feelings of “why me?” and “it’s not fair” often result in secretive snacking. Many of us have a long list of “forbidden fruits” or list of foods which we believe we should not eat.

It is not unusual for individuals to provide the following reasons for their inability to control their eating:

- “I have no willpower”

- “I’m weak willed”

- “my mother made me clean my plate when I was a child”

We often feel miserable as a result.

None of these problems are related to weight alone. Losing weight is not the solution. Even after losing weight, guilt, deprivation and misery can persist. The solution is to acquire the skills to control when you start eating and when you stop eating.

Control of eating is not always the entire solution to an eating problem. Quite frequently, there is a second component which must be addressed and that is the problem of “feeling fat” or body image. Body image problems result when an individual’s perception of their size is discrepant with their actual size. In other words, the individual feels fat even though they are not fat. For example, friends and family frequently tell them that they “don’t need to worry about their weight”, however, they continue to feel fat.

Individuals with ‘fat body image’ problems demonstrate behaviours such as:

- Asking their spouse “does this look fat on me?”

- Checking every mirror or plate glass window to make sure that their ‘fat spot’ is tucked in or covered up

- Standing in the back row to get their photo taken

- Wearing sweat pants and shirt to the beach

- Avoiding gyms, reunions, and exercise

Weight loss alone is not the solution to a body image problem. In fact, it can make the problem worse as the discrepancy between the size a person perceives themselves to be and their actual size becomes larger. Once a body image problem has been identified, it is necessary for the individual to start behaving “thin”, thus leading them to “think thin” and eventually to “feel thin”.

Most people who say they have ‘weight problems’ usually have some concerns about their willpower or lack of it. They are often accused by other people of lacking willpower. They are often scolded by others for not using it. What we know is that the control of eating is far too important to be left to willpower and conscious control and far too complex.

In Part II of this series, we will start by looking at what it is that starts and stops us from eating – the determinants of eating behaviour – and why it is that we have to eat in the first place. We will discover that “the real problem” has nothing to do with willpower.

[1] Ng, Marie et al. (2014, May 28). Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet, 384 (9945), 766 – 781. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8

[2] McPherson, Klim. (2014, May 28). Reducing the global prevalence of overweight and obesity. The Lancet, 384 (9945), 728 – 730. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60767-4

Recently, I decided to investigate the current scientific literature regarding behavioural approaches to eating control and weight regulation. I discovered the work of Dr. Brian Wansink, (Ph.D. Stanford 1990) who is the John Dyson Endowed Chair in the Applied Economics and Management Department at Cornell University, where he directs the Cornell Food and Brand Lab. He is the lead author of over 100 academic articles and books on eating behaviour. Kelly D. Brownell, Yale University, has hailed Dr. Wansink as “the Sherlock Holmes of food”.

Recently, I decided to investigate the current scientific literature regarding behavioural approaches to eating control and weight regulation. I discovered the work of Dr. Brian Wansink, (Ph.D. Stanford 1990) who is the John Dyson Endowed Chair in the Applied Economics and Management Department at Cornell University, where he directs the Cornell Food and Brand Lab. He is the lead author of over 100 academic articles and books on eating behaviour. Kelly D. Brownell, Yale University, has hailed Dr. Wansink as “the Sherlock Holmes of food”.